My Good Lord, Count Jean Mortain and Porcien-en-Rhetélois, I am Brother Isambart de la Pierre, a priest of the order of Saint Dominic. I congratulate your efforts to preserve the memory of the poor, innocent child of God, Jeanne. To that end I am willing to assist you. I witnessed her trial and death and so am thoroughly aware of all the details concerning this failure of justice.

Brother Isambart de La Pierre, Part I

CHAPTER 34

JEANNE'S ORDEAL IN ROUEN

I, Brother Isambart de la Pierre, priest of St. Dominic, live at Rouen's Saint Jacques Monastery. I am a witness to Jeanne's trial and death and am proud to say I became her confidant during her last months. I first met this girl in her prison cell at the castle of Rouen. Her trial was to begin on the following day, and the court ordered the dean of my monastery, Father Jean Massieu, to read its summons to her. I accompanied him, wanting to see this infamous person for myself.

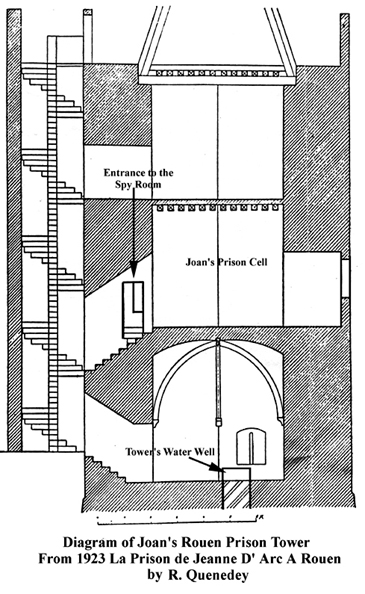

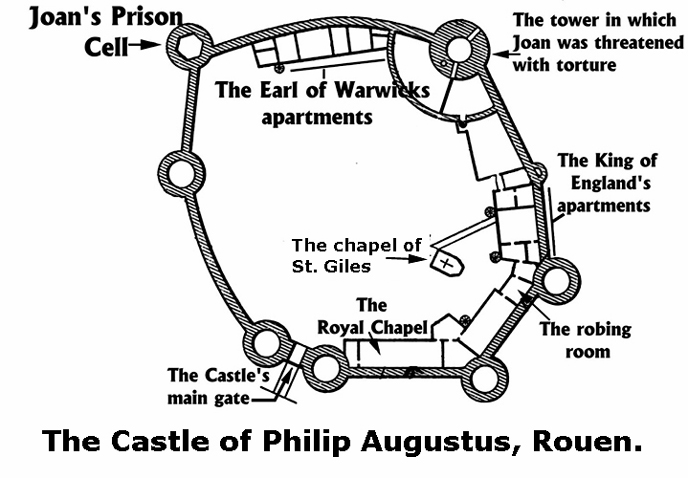

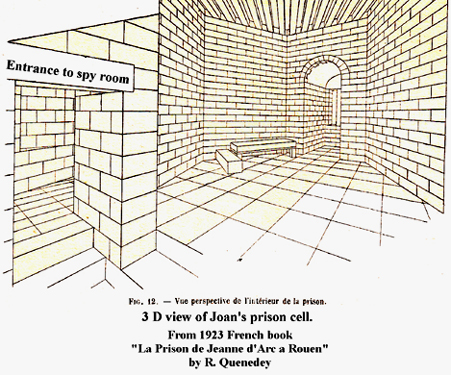

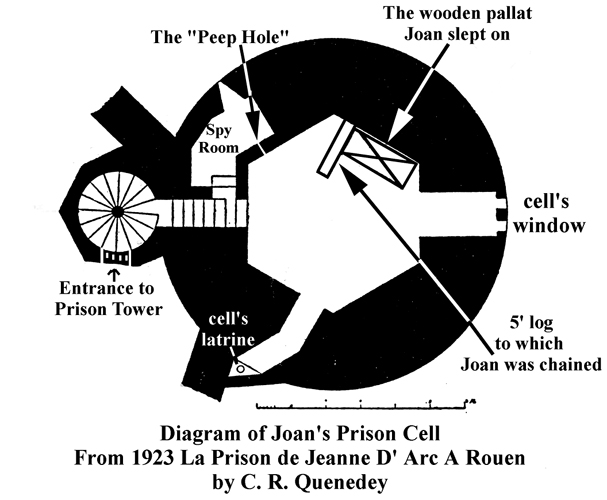

The castle courtyard is about three hundred feet across. Left of the stout twin towers of the stronghold's main entrance was the royal apartment where the young English King, Henry VI, lived. Directly across from these apartments was Jeanne's prison. To the east and only forty feet from her tower were the apartments of the Earl of Warwick. At the entrance of Jeanne's prison tower stood two heavily armed English guards. The massive old door's rusted hinges squeaked loudly as one of the soldiers struggled to pull it open. This door revealed a spiral staircase that circled up to the first floor. Coming off the stairs on the first floor were a short series of steps, which led up to Jeanne's cell.

As I reached the fifth and sixth step, there was a small irregular shaped room. This room had a peephole in the wall through which Jeanne's captors could spy on her. In the coming months it would be used extensively by Bishop Cauchon's man, Father Nicolas Loiseleur. He deceived Jeanne by passing himself off as a fellow prisoner. At other times, he disguised himself by covering his face with a hood and muffling his voice. Thus, he came to Jeanne at night to hear her confession and to be her spiritual advisor. Although Father Loiseleur was bound by the seal of confession, Bishop Cauchon placed men in the adjoining room to overhear her confession and use her words against her in court. By doing this, the Bishop committed a grave sin, because the seal of silence equally binds all who overhear a confession.

Two English soldiers stood on the seventh step in front of a wooden door. Once through the door, we stood in her cell: a hellish place that was dark, damp and bone chillingly cold.

She was kept in a hexagonal room about twenty feet across, sixteen feet from floor to beamed ceiling. Extending off her cell was a small alcove that had two slits in the masonry, each one foot wide by eight feet high. This served as a window that looked out over an empty field. The cell's latrine was found at the end of a dogleg hall. It was a dark and airless place filled with the stench of human waste.

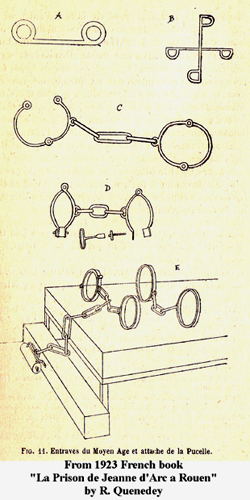

She was shackled hand and foot. Tight iron cuffs bruised her wrists. Around her waist she wore a wide iron band that dug into her hips, causing her much discomfort. Finally, Jeanne was forced to wear two sets of manacles, one just below her knees and the other around her ankles. A short iron bar between each pair of manacles prevented Jeanne from moving her legs. These devices caused her limbs to ache and swell. At the foot of her bed was a huge log. Her chain was attached to this and threaded through her foot and leg manacles, through the waist belt, and finally connected to the cuffs at her wrists. Because of these sadistic devices, her ability to move was greatly restricted. If she was lucky, the guards released her once or twice a day to use the latrine. The wardens removed these restraints when she was called to court, but before she left her cell they would clamp shackles around her ankles, which caused her to walk in short, halting steps.

Her jailers were men of the lowest sort: coarse, brutal and depraved. I had never met anyone more devoid of human decency than those five. They were always drunk and wasted their time with games and lewd songs. Their superiors encouraged them to mock and torment Jeanne. To amuse themselves they would push her from one guard to the next, or beat her, or torture her with vivid descriptions of death by fire. I witnessed this firsthand.

The first time I laid my eyes on her and saw her male attire and the cut of her hair, I was overcome with indignation. Glaring at her I thought, She must be what they say: a tool of Beelzebub!

When Father Massieu and I approached, she was chained to that great log, resting against the cold stone wall. Her somber eyes followed us as we drew near. In a business-like manner Massieu took the scroll from his sleeve and began to read:

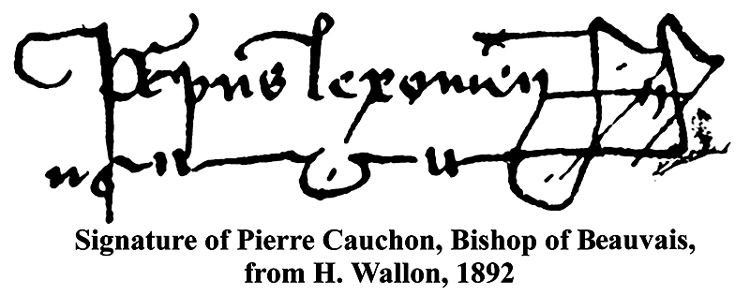

We, Pierre Cauchon, by the grace of God, Bishop of Beauvais, do summon you, Jeanne, commonly called the Maid, to appear before us, in the chapel of the castle of Rouen at 8:00 on the morning of Wednesday, February 21st, to answer the charges that are brought against you. Be it known that if you fail to appear before us, you shall be excommunicated.

Father Jean was rewinding the scroll when he asked, "Do you have a reply?"

Jeanne looked down at her chains. "Tell the Bishop I require him to summon churchmen of the French side equal in number to those of the English. If it pleases the Bishop, I would also like the assistance of counsel to help me answer his questions." She paused, folding her hands prayerfully together. "I humbly beg the Bishop's permission to hear Mass before I appear."

That evening, when I closed my eyes, I saw this impudent young wench in male attire. I realize with troubled mind that what I saw at our first meeting was superficial. I had judged her severely, believing she was all that the English had said. Yet, how many witches beg to hear Mass?

The Bishop did not permit either of us to say Mass for her, so next day Father Massieu and I led Jeanne to the court.

The scraping of her chains against the flagstone floor heralded her approach. The great doors of the Royal Chapel swung open, and from the shadows stepped the Maid. Those assembled, churchmen and leaders of Rouen, leaned forward, craning their necks to see 'the French witch.' In horror and dismay, they gasped almost in unison. Some of them covered their eyes. She was dressed entirely in black, in a page's costume. Her well fitting doublet, which accentuated her breasts, reached down just short of mid-thigh, while her tight fitting leggings revealed the muscular curve of her legs. Groans of disbelief swept the hall. Yet, Jeanne stood unflinchingly before them.

In the center of this large gathering sat Pierre Cauchon, the Bishop of Beauvais. On either side of him in a semicircle sat sixty ecclesiastical judges who would affirm his decision. The Royal Chapel of the Rouen castle was stark and stony-cold, with a few large windows through which sunlight entered. This morning an enormous, slanting shadow cast itself across the floor in the form of a cross. The center of this shadow fell directly on the small wooden stool for the accused.

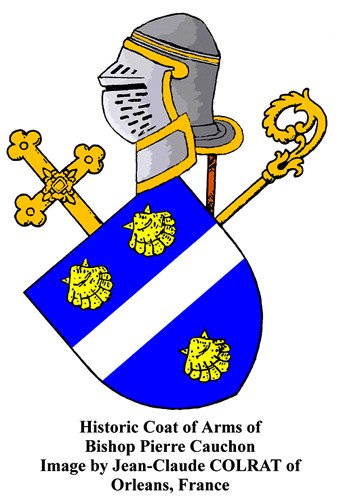

Bishop Cauchon, in his finest purple vestments, relaxed in his high-back chair. He was a large, well-feed man with an ample face. There was nothing extraordinary about his countenance; nothing that would betray his dark, sinister heart. Except perhaps his steel-blue eyes, which were normally just menacing but when he was angry, they pierced you like a knife.

The clatter of chains followed as she took her seat. With a glare that silenced the court, the Bishop formally opened the trial of Jeanne, the Maid.

"This woman, Jeanne, commonly called the Maid, having been taken within the confines and limits of our diocese of Beauvais, has committed many actions that have injured the orthodox faith." Cauchon began, his voice resonating impressively. "Therefore, considering the public rumor and common report, we decreed that the said Jeanne should be summoned to answer the inquisition in matters of faith and other points truthfully according to law." His gaze again traveled around the room as three clerks hurriedly wrote down his words, quills scratching in the silence. Turning to the Promoter he commanded, "Admonish this woman to unburden her conscience and to answer truthfully all that will be put to her."

The Promoter, Father d' Estivet, was a lean, wiry figure who kept his hair cut close and his face shaved. A hard man, insulting and overbearing, he was despised even by those who worked with him. Hand-picked by the Bishop for his zealousness, he was well suited for the role that he would play.

Picking up the weighty Gospel, he brought it before Jeanne. "We lawfully enjoin you to take the proper oath, with your hands on the holy Gospels and to speak the truth to such questions as will be put to you."

Jeanne took her time studying d' Estivet and the others that stared at her. Her soft voice echoed throughout the hall. "I do not know what you wish to ask. Perhaps you will ask questions on certain topics that I would not answer?"

The crowd groaned as the secretaries dutifully marked down her words.

D' Estivet crouched, his spittle spewing across her face. "Will you swear to speak the truth concerning the Faith and of which you know."

Jeanne calmly wiped her face. "Of my father and mother and what I have done since taking the road to France, I would gladly swear." She stiffened. "But concerning the revelations from God, these I have never told to anyone save my King. Even if I were beheaded for it, I will never reveal them, because they came to me in visions by my counsel! Yet, within eight days, I shall know certainly whether I might reveal them."

She lowered her eyes as she continued. "Throughout my life I have always tried to answer every question in a Christ-like manner. As far as I am concerned, the words that come from my lips must be acceptable to Jesus. And so if I need time to respond in this manner, I will say, 'Passez outre', pass on to another question.'"

Because she did not meekly comply, her judges went wild, shouting to themselves or at Jeanne. Others jumped to their feet vigorously shook their fists. Townspeople turned to each other in surprise. The record keepers appeared confused. Through this tumult, Jeanne sat patiently. Bishop Cauchon rose to his feet, his face red with rage. His voice careened throughout the room.

"We admonish and require you to take an oath to speak the truth in those things that concern our Faith."

While the storm raged on in the court and the judges continued to argue among themselves, Jeanne went to her knees in front of the Promoter and placed her hands on the Gospel.

"I swear to speak the truth on matters concerning the Faith," she told him. Then, she turned to the Bishop and added defiantly, "As to my revelations, which I have from God, I will not reveal them to any person!"

Jeanne returned to her seat. It took well over five minutes for order to be restored. I thought d' Estivet was going to hit her with the heavy Gospel! He restrained himself like the obedient dog he was and returned to his place at Cauchon's feet. The Bishop wisely decided to leave the matter of the oath for now.

"What is your name and surname?"

"In my own country I was called Jeannette, and after I came to France, I was called Jeanne. Of a surname I know nothing."

Adjusting himself in his plush chair Cauchon asked, "Where were you born?"

"In the village of Domremy."

The Secretaries scribbled in unison. Cauchon did not bother to cover his mouth as he yawned, exposing his yellow ragged teeth. "What are your father's and mother's names?"

Tears formed in her eyes and her voice trembled. "My father's name is Jacques d' Arc, my mother's Isabelle."

"How old are you?"

She looked at the floor, counting her age on her fingers. "I think, nineteen."

Jeanne would, at times, drive her judges to distraction by refusing to answer their questions, but would instead say whatever she felt like. This habit of hers would make the questions and answers of the trial record seem disjointed. Thus she added, "It was from my mother that I learned the Our Father, the Hail Mary, and the Creed, and from no other than my mother was I taught my faith."

Cauchon's expression changed. He knew a witch could not say the Our Father properly but would say it backwards. Leaning forward in anticipation he demanded, "Say the Our Father for us."

"Hear me in confession, I will happily say it." She answered.

This set off another tidal wave of protest. It was pitiful to see grown men of the cloth behaving like belligerent children. Repeatedly, Cauchon thundered above the din, "Say the Our Father for us! Now!"

Jeanne sat calmly, shaking her head. "I will not, unless you hear me in confession."

This was a masterstroke for an illiterate peasant! If Bishop Cauchon heard her confession, he could no longer be her judge, as he would be under the seal of confession. If he refused to hear her confession, he would be denying her the sacrament and thus go against church law. Cauchon changed tactics.

"We will give you one or two notable priests who speak French, to hear you say the Our Father."

"I will not say it to them, except in confession."

Again, Cauchon had to back down. Jeanne then demanded, "I want to be taken to the Church prison and have women guard me."

Cauchon was annoyed. "Strike last statement from the record! We, Bishop Cauchon, hereby forbid you, Jeanne, from leaving the prison assigned you in the castle of Rouen without our authorization, under the penalty of being convicted of the crime of heresy."

With the chains clanking noisily, Jeanne jumped to her feet. "I do not accept that prohibition! If I escape, no one shall reproach me for breaking or violating my oath, since I have never given such an oath to anyone. Why do you keep me chained and in fetters of iron? I should be held in a church prison, guarded by women and not by my enemies."

Barely able to contain his irritation, he answered, "You have tried elsewhere and on several occasions to escape. Therefore, that you maybe more securely guarded, we have ordered you to be kept in irons."

Placing her fist over her heart she openly declared, "It is true, I have and I still do wish to escape! Is it not lawful for any prisoner to try to escape?"

The crowd murmured.

Cauchon grimly motioned to her guards to come forward. He had them swear to guard her well, on penalty of mortal sin. He then addressed the Maid. "We command you, Jeanne, to appear before us tomorrow at 8:00 in the morning, in the robing room of the great hall of this castle. Remove the prisoner!"

Cauchon could see that the audience was being swayed. He knew too that if Jeanne could affect them, she could also influence the judges. The Bishop handled this by setting the next session in a small room, thereby forcing a reduction in the number of judges and preventing all others from witnessing the trial.

Once she was returned to her cell, the guards put her chains back on. Thus, she spent the long dark nights enveloped in the unseen terror of her dungeon, while her days were filled being hounded by her judges.